What does the ambient music reveal about me?

Weeks of tracking and recording the music playing around me reveals a lot more than just my favorite song

It’s been over a month since I first started my public ambiance experiment, and just a few hours ago, the experiment has officially come to an end. Someone had responded to one of my tweets asking when I might conclude the experiment, which felt like reason enough to stop it right then.

The experiment had honestly faded in and out of my mind during its five-week run. The tweets and Spotify playlist storage were automated in the background, so the only reminder I had that every song was being publicly documented was an occasional like notification from Twitter, usually a musical artist fan page liking a tweet that included the artist’s name.

It was a fun run, and once I had all the initial bugs sorted out (shifting from updating my Twitter bio to sending a tweet instead, and separating the Spotify and Twitter processes rather than daisy-chaining them), it ran relatively smoothly.

I’m sure not every single song that played around me was documented; there were several occasions where I saw my phone did not detect a song, either because the clip was too short or it simply couldn’t find a match. There were also plenty of false-positives; not necessarily misidentified songs, but original songs that my phone for some reason thought were remixes or covers from tribute bands.

Still, the final data certainly is impressive. The IFTTT recipe to tweet out a song ran 584 times since I first turned it on on June 1; the recipe to add a song to a Spotify playlist ran 341 times since May 27 (oftentimes Spotify could not immediately find an exact song match given the title and artist, and therefore couldn’t add it to a playlist; many of the songs that were added are covers and remixes as well).

As I said in my original post, I was not sure what I was trying to accomplish with the experiment, but looking back, I will say that it encapsulated far more than I had anticipated. At the experiment’s inception, I had only thought of the ambient music playing at my work and Spotify songs playing out of my phone speakers. I had grossly underestimated my exposure to music. TV shows, movies, commercials, even the tiniest and shortest of soundbites and jingles captured, identified and published. More importantly, the patterns in the music are identifiable. While my Spotify music playing is random and self-selected, other things aren’t. Based on the order in which I was hearing songs, followers could piece together what radio station I was listening to or what TV show I was watching. Case-in-point, I just finished binge-ing the new season of Stranger Things. Not only could someone tell based off my tweets indicating the Stranger Things theme was playing around me, but the subsequent order of the 80’s music could easily reveal not only what episode I was currently on, but how far into the episode I was.

The same goes for music in movies. A certain combination of songs could identify what trailer just played, or where I am into the movie itself. And beyond just what I’m doing (watching a specific movie), one could assume where I was (at the movie theater).

“Mask Off” and “Public Service Announcement,” courtesy of the “21 Bridges” and “Hobbs and Shaw” trailers, respectively, during an afternoon at the movies.

Let’s take this to an extreme data-processing situation: based off the order and timing of various soundbites, a data giant could predict that I’m seeing a specific movie, and that I’m an hour into the movie. Cross-reference that with info about how long the movie is, it could predict that the movie would be getting out around dinner time. Cross-reference that with my search history, transaction history and location history, and the data giant knows to offer me a specific restaurant recommendation in an hour and a half when my movie gets out.

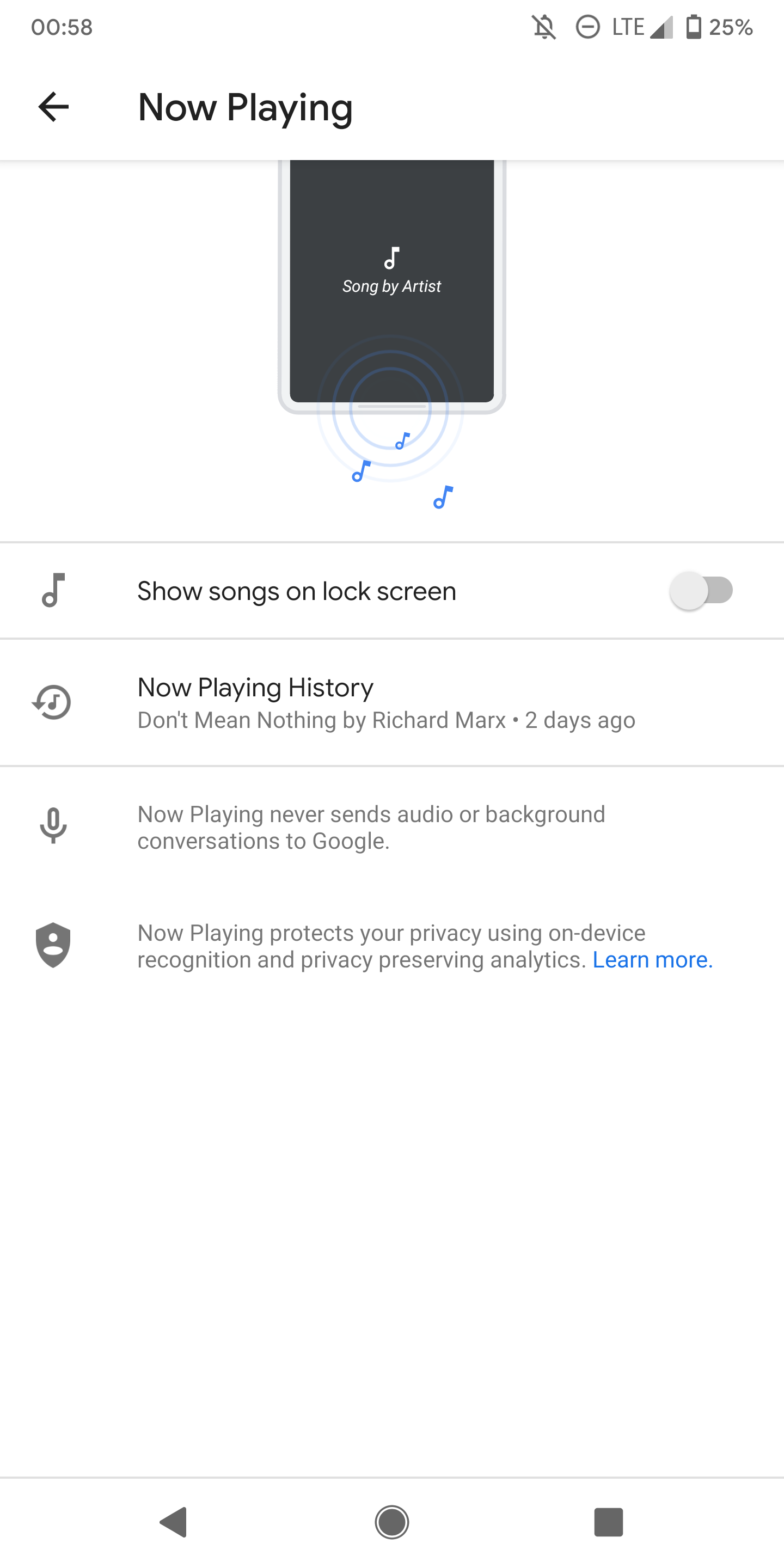

Now, with the experiment done, I’ve turned off the listening feature on my phone as best I could. While it seems like the feature is off, at least visible to the user (the last song documented in the “Now Listening” history was in fact the last song playing before I stopped the experiment), there doesn’t appear to be a conclusive way to disable the feature. I’ll include a screenshot of the page below; the Now Playing settings has a single toggle to turn off “Show songs on lock screen.” Whether that means the phone is no longer listening or it’s simply not displaying the results anymore is unclear (Android has a history of collecting data in the background even if there’s no front-end way to view the data). And, regardless of what the page says about privacy, I remain convinced that there’s simply no way an enormous library of song IDs could possibly be stored offline on my phone without consuming massive amounts of storage, and that the audio is in fact being funneled through Google’s servers.

It’s not entirely clear if it’s no longer listening, or just not telling you it’s listening.

So what did this whole thing accomplish? Well, as I stated in my original post, one way to look at this experiment was me taking back control of my data, by actively deciding to publicly disclose what big data companies may or may not be doing behind the scenes already. For years, there’s been countless accusations of companies such as Facebook tapping into the microphones on users’ phones to record ambient noise, listening for nearby music or even television commercials to better target advertising (these theories have largely been debunked, with corresponding relevant ads chalked up to coincidence and other less-intrusive, though perhaps more creepy, data analytic processes). Still, this experiment shows just what kind of data could be collected by a data giant like Facebook or Google, and more importantly, what that data can reveal beyond just what our favorite music is, from what a user is currently doing to where a user currently is.

It’s a neat parlor trick, but I think I’ll keep this feature disabled from now on.